CloudFormation vs. Terraform.

a

There is a time when every project that uses a cloud computing service has a difficult choice to make - should we automate the infrastructure or not?

a

There is a time when every project that uses a cloud computing service has a difficult choice to make - should we automate the infrastructure or not?

Immediately after, another question pops up - how should we do it? Should we use a dedicated tool (AWS CloudFormation, Azure Resource Templates, OpenStack Heat or Google Cloud Deployment Manager) or a provider-agnostic solution? And then - immediately after a surprise comes in - at first glance, there is no other tool like Terraform available on the market (but there is - it is called Foreman ![]() ). So we have a good tool, built by amazing people (HashiCorp) which does not rely on any particular cloud - problem solved? Not entirely.

). So we have a good tool, built by amazing people (HashiCorp) which does not rely on any particular cloud - problem solved? Not entirely.

As a grown up, you know that like the ORM does not let you change database on the fly, Terraform will not let you automatically switch your cloud provider for your entire system. From the other hand - you fear vendor lock-in, and for sure you are considering how to design and prepare disaster recovery scenarios. A lot of unknowns, isn’t it?

I would like to show my rationale for a new project and infrastructure for which I, among others, was responsible. The motivation which drove us towards a pure CloudFormation setup, the reason behind our bet on AWS, and the motivation behind the decision to drop Terraform.

Keep in mind that all remarks and comments pointed in this article are constructive criticism - it does not change my opinion about companies that created those tools at all. I have huge respect for both for AWS and HashiCorp - the work they have done, especially in tooling and cloud computing landscape is outstanding. As a user of AWS Services and HashiCorp tools I am grateful for the work they did.

If you do not have experience with CloudFormation or Terraform - please read either amazing documentation or any other introductory article. I will assume your basic knowledge about these two.

Terraform is not a silver bullet.

When I evaluated Terraform, it was before 0.7 release. According to the definition, it is:

... a tool for building, changing, and versioning infrastructure safely and efficiently. It can manage popular existing service providers as well as custom in-house solutions.

It is a tool built by practitioners, to support the infrastructure as code approach. It is built as an orchestration tool, focused on visibility (execution plans and resource graphs) and change automation, with minimal human interaction required.

Sounds great, and what is even more important it is cloud / provider agnostic by design. This is a huge plus, especially when you need to consider either mixing public cloud with on premises or a scenario with multiple cloud providers (e.g. for disaster recovery or due to availability requirements). What is also key, it does not focus on cloud APIs only - it incorporates various 3rd party APIs and Cloud provider API in one place, enabling interesting scenarios - e.g. creating infrastructure inside cloud provider, connecting it with your storage solution on premises and combining it with an external DNS provider.

One of its assets is the DSL - HashiCorp Configuration Language (HCL). In my opinion it is not a revolution, but an evolution in right direction. Still declarative, but more expressive and at the same time more concise than JSON / YAML formats. Terraform is internally compatible with the JSON format. I will not dive into details, because they are extensively covered in the documentation: https://www.terraform.io/docs/configuration/syntax.html. One thing worth pointing out - it is not a valid programming language, and we will talk about it soon as well.

So far so good. But before making a final decision I wanted to check its state and see how it “feels”. The gave me a whole new outlook. First of all - from my perspective that tool is not as mature as I would like to see it. It is in the infancy stage - I have scanned the Github repository just for bugs related to AWS provider and uncovered a long list. It is not a definite list (probably many of them were neither confirmed, nor triaged / prioritized). But it gives an answer how rapidly the tool evolves. Second thing - which did not affect me directly, but I heard horror stories - there are some backward incompatible changes from version to version. Again - it is totally understandable, taking into account that tool is below 1.0. Still it was not suitable for my needs - I wanted a stable and tested solution, that will cover AWS Services for us (so cloud agnostic does not add anything for us, we discuss this later).

What struck me the most is how it works. It does not use CloudFormation, but the AWS API - which has several consequences. It’s impossible to perform a rollback, when something goes crazy. The usual workflow is slightly different from the CloudFormation one- first, we need to plan our changes, then we need to review them and decide - should we apply or not. With CloudFormation it is possible to review changes as well, but if everything goes hazy for any reason (and it eventually will - trust me ![]() ) it will be able to roll-back that change and return to the previous state.

) it will be able to roll-back that change and return to the previous state.

Here lies one more disadvantage - Terraform is highly opinionated. It requires and assumes various thing regarding your workflow. It adds impedance mismatch and requires effort regarding knowledge exchange and learning an additional tool. Last, but not least - it is stateful. In the version I’ve evaluated there was no easy way to share and lock state in a remote environment, which was critical from my point of view (and in this case neither storing state on S3 or inside a repository was an acceptable solution).

Up to that point I did not ditch Terraform yet, but desperately searched for an alternative. Enter CloudFormation.

CloudFormation is not a hostile environment (neither a perfect one).

JSON or YAML - choice is yours, but choose wisely!

JSON or YAML - choice is yours, but choose wisely!

Inside the company where I was building the new infrastructure, CloudFormation was used across the development and operations departments. I heard horror stories too, and wanted to be prepared for surprises before starting the project. So I spent some time with that beast. And guess what? It is not as ugly as I initially thought.

The obvious advantage is better support for AWS services than any other 3rd party tools. When AWS releases a new service in most cases it is already supported inside CloudFormation, at least partially. However, there are some elements that either do not make sense for CloudFormation (e.g. registering DNS name for a machine spawned inside auto-scaling group) or are unsupported (e.g. ACM Certificate Import).

According to the documentation - CloudFormation is stateless, but that is actually a tricky concept. It is stateless, except when it is not. ![]() From your perspective, you do not need to bother about state management. But it is not entirely true - inside the service it preserves a stack of operations invoked inside your cloud (called events) and it connects them with resources. Updates are based on that state. Another point are exported outputs - globally shared inside the same region and AWS account. That means that you cannot create the same stack twice based on the declared definition, because it will collide with the defined outputs.

From your perspective, you do not need to bother about state management. But it is not entirely true - inside the service it preserves a stack of operations invoked inside your cloud (called events) and it connects them with resources. Updates are based on that state. Another point are exported outputs - globally shared inside the same region and AWS account. That means that you cannot create the same stack twice based on the declared definition, because it will collide with the defined outputs.

What about the learning curve? Well it turned out that it depends. Definitely it is not as hostile an environment as advertised. If you google for it - you will see how much people hate it. Of course, those people did not lie and in each accusation lies a grain of truth, but the situation had drastically changed after one announcement.

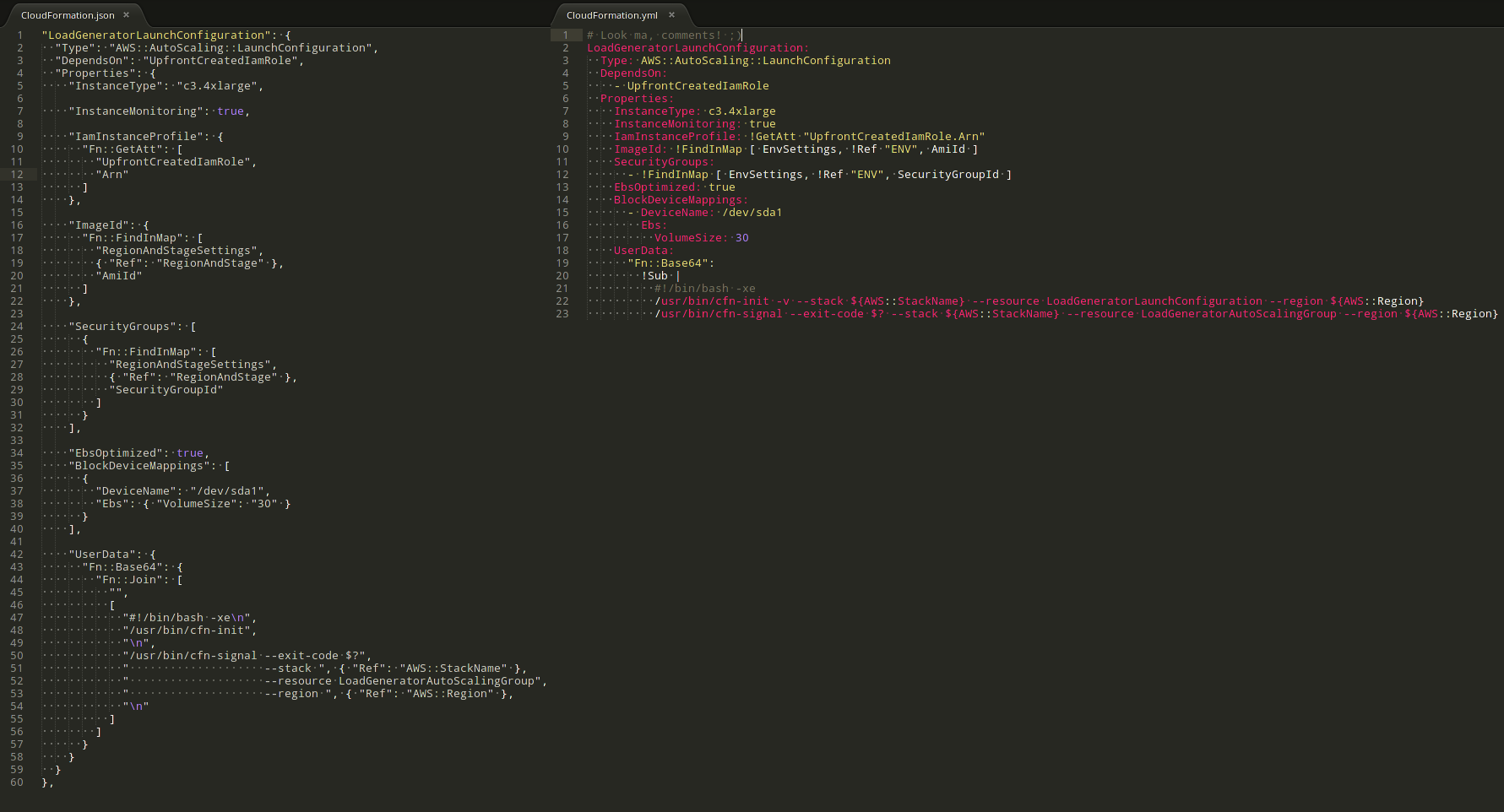

The announcement was regarding the release of YAML format support in the CloudFormation templates. Previously you could use only JSON for that. In my opinion it is a game changer. If you do not believe me, look at the screenshot posted above - the difference is at least noticeable. I wrote templates in both formats and the difference is huge, starting from really basic stuff like added support for comments (yes, JSON does not have comments at all), multi-line strings (yay, no more string concatenation! This is really helpful for "AWS::CloudFormation::Init" sections and similar), to the smaller stuff like better support for invoking built-in functions. And last, but not least - it is less verbose and less painful to modify / refactor. In case of JSON it is really hard to refactor huge chunks of code, trying to make it readable and still preserving syntax validation (and CloudFormation validation API supports slightly malformed JSON, so you need to have two layers of checks).

Is it all? Not entirely. I mentioned that there are couple of elements not supported directly in CloudFormation, making operations really painful and semi-manual. It turned out that you can either work around it with some well-known hacks (focusing e.g. on "AWS::CloudFormation::Init") or with new and strongly advertised concept that I wanted to test in practice - automating operations with the AWS Lambda service. It turned out that with help of SNS, SQS and AWS SDK I was able to glue the services in an elegant way. In serverless and event-driven fashion.

Can you guess all the logos present in the picture?

Can you guess all the logos present in the picture?

Vendor lock-in is a thing.

In this place I would like to stop and point out a real threat - vendor lock-in is a thing. It is neither a myth, nor a boogeyman. Relying heavily on CloudFormation and gluing it with AWS Lambda should be a deliberate choice. It is a considerable liability, if you are considering moving out from the cloud.

If you are not Snapchat, and do not have 2 billion USD for a certain cloud provider, for sure you have considered what if we want to use a different provider or use physical infrastructure for our product. Moving either in or out between clouds or cloud and physical is a big project per se, sprinkling it with additional services provided by your cloud complicates it even more.

In most cases, if you are careful, it is rather an infrastructure and operations effort. However some services looks so shiny, so easy to use, so cheap (like AWS Lambda) and incorporating them looks like a really good choice. Except when you consider moving out from particular provider and you need to dedicate additional development and operations effort for such migration.

In my case the decision was simpler than you might think. When moving out from physical data centers to the cloud of choice - AWS was chosen as the most mature. There is no plan for migrating out of the cloud (this was not the first project moving there, a huge development effort has already been spent, including building custom services on top of AWS API) and the physical solution is not as elastic and cheap choice as you may think. Tests done in the cloud already confirmed, that even for a demanding domain (ad tech) a cloud provider will be sufficient. And it offered more than the physical world.

So you can consider it as a deliberate vendor lock-in, with all of its consequences. I was in the physical world, I saw how it worked and felt, and still needed more - the cloud was the right choice. But it is not a usual path to take.

CloudFormation pitfalls.

I have already scratched the surface, but even though so far I am happy living with CloudFormation - it has sharp edges too.

The most significant problem, discussied widely over the internet is the horror stories regarding updates and changesets for CloudFormation. I did not have any problems with a list of changes generated by the service, which would hide the actual operations. However an update is harder than you might think, in most cases because of replacements. It is hard to believe sometimes how a simple change may cause a domino effect leading to rebuilding of some unrelated elements. And killing elements is problematic.

Exported outputs are another topic. Those globals in the stateless world are as helpful as they are annoying. On one hand, they are a neat way to connect between stacks, on the other - it is really easy to tangle stacks together and introduce dependencies, which are hard to reflect in the creation process.

Another painful element is naming (I will not repeat that old joke about hard things in computer science, but we all know it). The name should reflect the purpose, but also in many cases the location - for your convenience and better readability. In such cases you have to remember which services are globally available and which are not (Route53, IAM and S3). And that is not the end of story, because for example - S3 is a global service, and at first glance you do not need to put a region in the name. However, the bucket location makes a huge difference in a cross-region replication scenario, and having region name is really helpful. Decisions, decisions.

Another pain-point related to naming are limits. Strangely enough they are not validated via the API, only checked during the stack execution are various name length limitations (e.g. the 64 characters limit for ELB name). You will know them by heart after couple of failures and rollbacks - just be prepared. ![]()

And last but not least - you want to always be compliant with CloudFormation standards to start and stay small. Always use the types provided by CloudFormation, which help the validation API. Prepare your own naming convention (also for tags) and stick to it as much as you can. Keep stacks as small as possible and split them in two dimensions - by responsibility (e.g. component) and by common modification reason (e.g. they are often modified together). Use exports with caution (naming convention also helps tremendously here).

Summary

In my case, when a deliberate vendor lock-in was available as an option, so far I am not regretting choosing CloudFormation. I was able to build the infrastructure and tools on top of a solid and battle tested service, fully compliant with the chosen cloud computing provider. However I know that it is not the usual option for everyone - I hope that deepened approach to the topic and my rationale will help you make right decision. Remember: there is no universal solution here. In case of any doubts or if you would like to hear more about certain topic feel free to reach out to me in the comments below or directly at my contact email.